Learning Zone - Archive Discoveries

From time to time we share stories from the archives, usually records we have discovered that have excited us as genealogists. We share these discoveries in our newsletter and/or on social media.

We will be selecting some of our favourite discoveries and sharing them on this page. Of course, we will still be posting on social media and that will include posts which are not shared here. Also, if you use our services you qualify for our free newsletter. There will be a link in the email we send you when you first order.

Sheriff Court - Romantic drama in 19th century Scotland

Sheriff Court - A Victorian Valentine

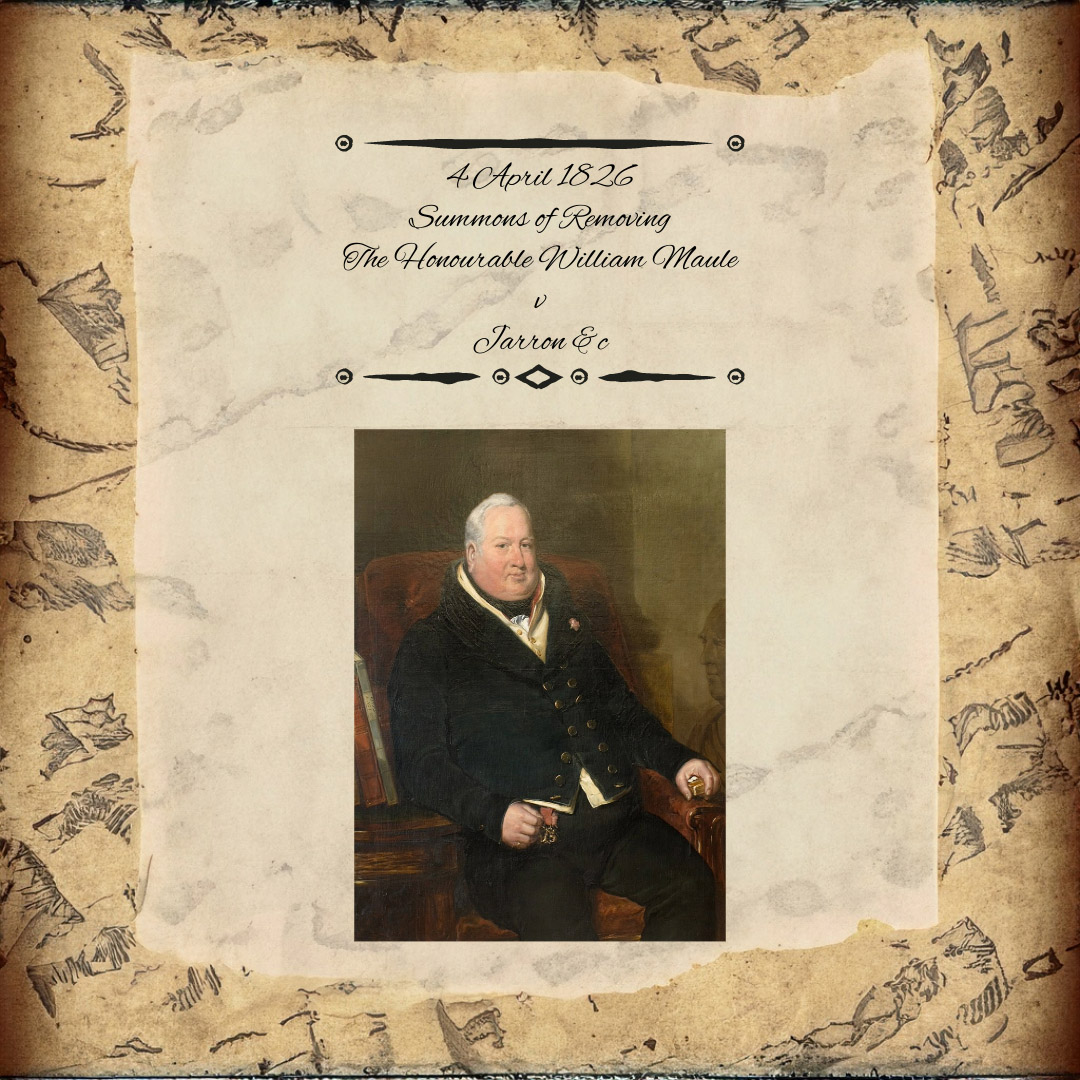

Sheriff Court - Maule v Jarron

Sheriff Court - A marriage register is not always a register of marriages

Sheriff Court - Families go to court!

Crown Office Opinions - Justice for Elizabeth

Crown Office Opinions - Duels did not always take place at dawn!

Statutory Registers of Deaths - Death during construction of the Forth Bridge

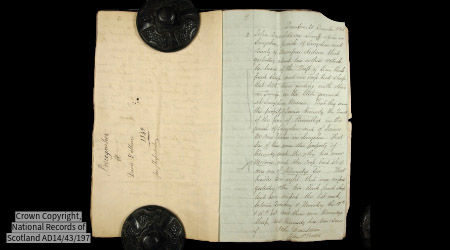

Register of Sasines - Finding Elizabeth's father

Sheriff Court - Romantic drama in 19th century Scotland

Who was Barbara Heatlie? How did her parents meet, and why was there a court case? In this video, discover the story of Agnes Heatlie and Arthur Bell from Jedburgh Sheriff Court records. Learn how to discover your ancestors using Sheriff Court records.

Sheriff Court - A Victorian Valentine

In this video extract, Tessa Spencer from the National Records of Scotland highlights a Victorian Valentine card that was presented to Paisley Sheriff Court as evidence. This was evidence in the case of Lindsay v Steel, which can be seen in our index here.

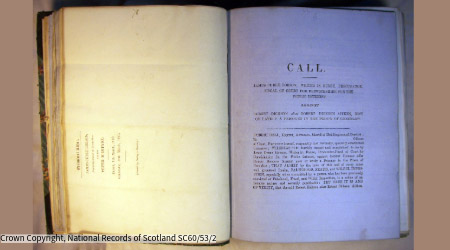

Sheriff Court - Maule v Jarron

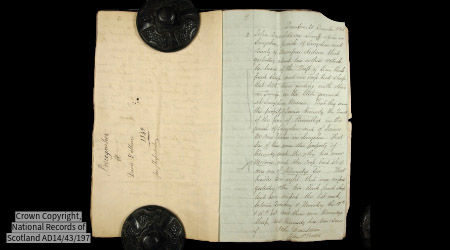

One of my favourite tasks when I visit the National Records of Scotland is to search Sheriff Court process boxes. These are boxes of paperwork, generally relating to the ordinary or civil court.

Most of the time I am searching unindexed, uncatalogued pre-1830 boxes and the cases are many and varied. On this occasion I was working through Forfar Sheriff Court looking for a 'paternity' case which it was hoped would solve a client's brick wall but I must confess I was often distracted by all of the other interesting cases.

For example, here are some notes from a case dated 4 April 1826 found in box SC47/22/648. The case is entitled: 'Summons of Removing, The Honourable William Maule v Jarron &c.' This is what you and I would call an eviction case. You can see William Maule in the picture.

Untying the nearly 200-year-old piece of string we learn more. The case is against Alexander Jarron, shoemaker at Craigton, Susan Paton residing there, George Sheriff, shoemaker at Craigton, James Carrie, farmer at Craigton, George Carrie, weaver at Craigton and Andrew Hay, merchant in Craigton.

This is perhaps lesson number one of working with loose paperwork when you have no index. What the clerk wrote on the outside of the bundle two centuries ago may not be very detailed. It is important to open the case to see who else is mentioned inside. So what more do we discover?

The opening paragraph tells us more about the individuals. Susan Paton is described as 'relict of the deceased William Crawford, labourer sometime at Craigton'. George Sheriff, shoemaker is designated 'son of the deceased George Sheriff sometime weaver at Craigton'. We also learn more about George Carrie, who is described as a 'weaver at Craigton son-on-law of the deceased George Watt, late weaver at Craigton and representing him'. Although this is not what I am looking for, it is still exciting. As a genealogist, I know that one day this is very likely to solve someone’s mystery. To have names, residences and family relationships in this period is a treasure to find.

Why was the case brought about? The pursuer, William Maule, claims that none of these people have any ‘tacks’. A tack is a Scottish term for a tenancy or property lease. These legal documents can be very useful to a family historian, or as we see here the absence of one can be useful too.

What I find interesting is that the 'Panmure Testimonial', also known as the 'Live and Let Live Memorial' was erected to commemorate the generosity of the said William Maule, who did not evict tenants from his land in the 1820s following a bad harvest. I now have more questions. Were these families evicted? What happened to them and do they have descendants? The 1841 census certainly shows that a James Carrie, aged 74, was a farmer at Craigton so perhaps William Maule did not follow through and allowed the families to stay in their homes.

Do you see what I mean about getting distracted? How can this help you trace your family history? First of all, use our indexes to find out if we have already indexed what you need. What if there is no index? Use Sheriff Court roll books or minute books to discover if there was a case of any kind; then search the boxes to find it. It is not for the faint-hearted but the process is very enjoyable so if you can plan a trip to the National Records of Scotland and see what you can discover.

Many tacks or similar legal agreements were registered in the 'Books of Council and Session' so it is also worth checking these; especially as many are indexed. To find out more check out our Learning Zone section 'Registers of Deeds'.

Registers of Deeds |

Registers of Sasines |

Scottish Paternity Index |

High Court of Justiciary |

Registers of Deeds |

Registers of Sasines |

Scottish Paternity Index |

High Court of Justiciary |

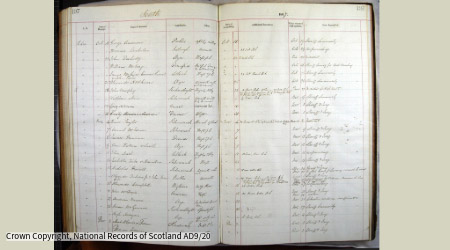

A marriage register is not always a register of marriages

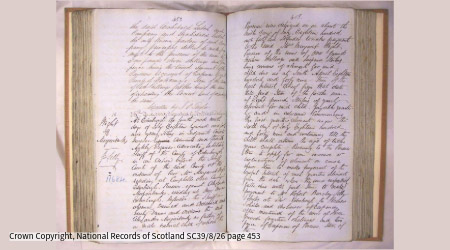

It is always important to think about what a document is telling you. Ask yourself why it was created, by whom and when.

For example, the church records of Newtyle in Angus, Scotland seem to record the marriage of Thomas Spence and Ann Ramsay. Why do I say ‘seem to’?

ScotlandsPeople provides access to the registers of the Church of Scotland, known as the Kirk. To be ‘regularly’ married by a minister the banns had to be proclaimed in the church. A record of the 'banns' being read was made by the Kirk.

These church registers had no standard format and varied from parish to parish. Sometimes we see clearly the dates the banns were proclaimed to the congregation and then the date of the marriage. We may even see the name of the minister. This is great because it’s clear.

What about the marriage of Thomas Spence and Ann Ramsay? We find this recorded in the Newtyle register and it does say 'Register of Marriage' at the top of the page. We see 24 January 1825, "Thomas Spence and Ann Ramsay both in this Parish". It is certainly not a detailed register but is it safe to conclude that this couple were married on or soon after the 24th of January?

Truth be told, many of us would accept this. None of the entries on the page give dates for the banns being read and another date that the marriage took place. All of the entries are similar to Thomas and Ann's.

I have been working through Forfar Sheriff Court records recently. Within the boxes of court records I have found an extensive case, Ramsay v Spence. You guessed it, this is Ann Ramsay and Thomas Spence. In a case which took over a year to reach decree, Ann pursued Thomas for the aliment of a male child born on 15 January 1826.

We read in the summons, "Whereas it is humbly meant and shown to me by Ann Ramsay residing at Millhole Pursuer That Thomas Spence at Castleton or Castlenairn, Defender having, under promise of marriage, seduced the Peruser to submit to his unlawful embraces, she thereby become pregnant...".

On 18 February 1827 George Browster, Session Clerk of the Parish of Newtyle, aged 50, declared, "That the Parties lived near to one another but the Deponent cannot say for how long a time nor when the Defender removed from that place of residence. That upon the twenty fourth of January Eighteen hundred and twenty five the Deponent published banns of marriage between the Parties in the Kirk of Newtyle at the desire of the Defender and he paid the Deponent the proclamation fees. That at that time the parties were living about a park breadth from one another...".

On the same day James Lawson, farmer at Castlenairn, stated "That the Defender was a servant to the Deponent for the half year after Martinmas Eighteen hundred and and twenty five That James Ogilvy the Deponents Grieve applied to him about the end of that winter for one pound to the Defender in part of his wages to enable him to give the Pursuer some money towards the inlying expenses of her child that the Deponent refused to give Spence the money as he had not then earned his wages...".

This was one of the key pieces of evidence against Thomas Spence. He, however, mounted a defence. In part, this was to reduce the amount of the aliment. On 22 March 1826 we read [about Thomas Spence] "He is quite a young man. His employment is the humble service of working a pair of Horses at the wages of £8 for the year. Supposing he were the father the aliment claimed is extravagant...".

In November 1826 we read "At that time the defender was not above Eighteen years of Age, and acknowledged he was unwarily induced to give up his name for proclamation of banns. On consulting with his relations, and reflecting on what he was about, he was convinced of the impropriety of his conduct and declared off before sealing his ruin. So wretchedly poor was he that he had not wherewithal to pay the proclamations."

We learn through this convoluted case that Thomas and Ann did not marry. The register is a register of proclamations but not marriages.

The good news is that we have indexed this and other ‘paternity’ cases found in these boxes and they are now part of the 'Scottish Paternity Index'.

What can you do though, if you did not have a case like this to shine a light on the situation? First of all, look at the whole page. If all but one entry explicitly gives a date of marriage be wary of the entry that does not.

If, like this register from Newtyle, it is not clear, make a note of that. I would say that the majority of the time a couple who were proclaimed to be married were in fact married but look for supporting evidence. For example, do the couple have children baptised? If they do not, ask yourself why not. If the couple survive until 1851 are they recorded as married or widowed on the census? Similarly, if they lived until 1855, what information is given on the death certificate? Can you find a gravestone for the family?

The takeaway: a marriage register is not always a register of marriages.

Search the Scottish Paternity Index |

Kirk Session Records |

Finding Paternity Cases in Sheriff Court Records |

New to Scottish Indexes? |

Search the Scottish Paternity Index |

Kirk Session Records |

Finding Paternity Cases in Sheriff Court Records |

New to Scottish Indexes? |

Sheriff Court - Families go to court!

Part of the joy of being back in the National Records of Scotland regularly is browsing through boxes of Sheriff Court records. I ordered out some boxes from Forfar Sheriff Court to search for an affiliation and aliment case. While searching, however, I found something a little different but packed with genealogical gems.

Searching a box of Forfar Sheriff Court processes (SC47/22/656), I found a petition dated 19 March 1827 relating to the McNaughton family of Dundee. In September 1821 Helen McNaughton married Robert Turnbull. Sadly, Robert died only a few years later in 1825. Helen returned to live with her father but died sometime prior to 19 March 1827.

After her death, there seems to have been a family dispute regarding her belongings. They are described as 'moveable' as these were things like a chest, a chair and a bed. Helen's siblings took Helen's 'natural' son to court over these possessions.

The petition (dated 19 March 1827) reads:

"Unto The Honourable The Sheriff Depute of Forfarshire and his Substitute: The petition of John McNaughton Junior Carter at Seafield Dundee, James McNaughton, and Isabella McNaughton or Young spouse of Robert Young Mariner both residing at Seafield, and the said Robert Young for his interest, Children of John McNaughton residing there and nearest of kin to the deceased Helen McNaughton or Turnbull Spouse of the also deceased Robert Turnbull - Humbly Sheweth, That the said Helen McNaughton died upon the [blank] day of [blank] last without leaving any settlements of her movable estate & without any lawful issue of her body. - That she left a natural son, Peter or Patrick Fisher Mariner in Dundee but he is not entitled to succeed to any moveable property with the said Helen McNaughton may have died possessed of, And the petitioners as nearest of kin to her are entitled to take up the succession & are in cursu of getting themselves confirmed executors to her. - That the only moveables left by the said deceased Helen McNaughton are a few articles of household furniture standing in the room of the house belonging to the said John McNaughton Senior, which the deceased occupied & of which room the said Peter or Patrick Fisher has surreptitiously obtained the key in order to prevent the petitioner from taking possession of them."

We see next a list of moveable possessions (which I have not transcribed) but includes 'tongs', a 'round hardwood table' and '2 feather pillows with slips'. We then see the point of the petition:

"May it, therefore please your Lordships to appoint this petition to be intimated to the said Alexander Bruce and Peter or Patrick Fisher that they may lodge answers thereto if they any have within a short space after service With Certification and at same time & untill the further orders of Court to Interdict prohibit & discharge the said Alexander Brice & Peter or Patrick Fisher & all other in their names on for their behoof from interfering with, carrying away, or selling the articles of furniture before mentioned, & any others of household furniture which belonged to the said deceased Helen McNaughton. - And on again advising hereof with or without answers to declare the said Interdict perpetual against the said parties."

On 21 March 1827 a warrant was granted and delivered to Alexander Bruce & Peter or Patrick Fisher. They had a short time to lodge answers in the case. We are told that on 3 April 1829 no answers had been lodged and the petition was granted the next day. At the time of writing, I am not sure what happened next. There does not seem to be a testament dative on ScotlandsPeople. It may be that as I continue to search this series I will find the next stage in this family feud.

As we search for our client's case we do take note of all affiliation and aliment cases we find. We have found a few so far and these have now been added to our index. Helen's husband was quite wealthy (his will is on ScotlandsPeople). People who had money, land or businesses often show up in the court records and when they do we can find vital clues to our ancestry.

Court of Session Records Index |

Registers of Deeds |

Registers of Sasines |

Finding Paternity Cases in Sheriff Court Records |

Court of Session Records Index |

Registers of Deeds |

Registers of Sasines |

Finding Paternity Cases in Sheriff Court Records |

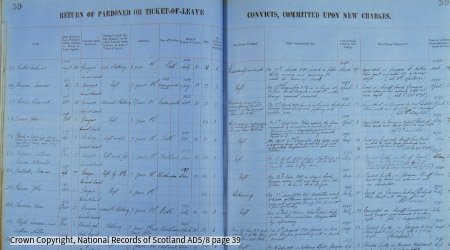

Crown Office Opinions - Justice for Elizabeth

We have really enjoyed working on our Crown Office Opinions project. They are a fascinating insight into early 19th-century cases that didn’t go to trial. The Crown Office Procedure Books index on our website covers all cases referred to the Crown Office for an opinion. This includes all High Court and all Sheriff Court jury trial cases as well as others that went to court. What about the cases that did not go to trial?

Here we have the case of Elizabeth Trainer or Cook in 1825. Note that the outcome was there were ‘No proceedings’. What did Elizabeth do? Why was the case not taken to court? Can we find out more about Elizabeth? If this is your ancestor I am sure you would want to know more!

Catalogued just as 'Opinions' and referenced AD13 by the National Records of Scotland, these contain a hidden treasure trove of information.

So far it appears that all cases that were returned as 'No proceedings' between 1825 and 1833 have paperwork in the AD13 files. We will continue researching the post-1833 records to assess what survives.

What then about Elizabeth Trainer or Cook? What is her story?

The Crown Office Procedure Book (AD9/1 p. 17) tells us that the Crown Office received her case on 20 January 1825. Her crime? Assault. The Jurisdiction is given as Edinburgh. On the 25th of January 1825 her case was returned with the opinion 'No Proceedings'. Although interesting, it does not tell us a great deal.

AD13/35 are Edinburgh Opinions for January 1825. Within this record we discover a lot more. We read in the petition:

"That on Wednesday last the 5th of January Current when Hugh Johnston, Pensioner at present in Edinburgh was in the house of John Cook, Packman Residing in Walkers Close, Grass Market of Edinburgh, Elizabeth Trainer or Cook wife of the said John Cook, did wickedly and maliciously assault and attack the said Hugh Johnston and strike him violently on the head with a bottle, whereby he is severely cut and wounded to the effusion of his blood and danger of his life and if he dies she will be guilty of the crime of murder; in these circumstances the present application is made to your Lordship to the effect aftermentioned".

Within the paperwork, we see that Elizabeth was committed to prison on 11 January 1825. In theory she should have been sent to the Tolbooth but it is noted that she was 'allowed to be detained in the Police Office'.

On 10 January 1828 a doctor provided a medical certificate and stated that "Hugh Johnston Petitioner lies Dangerously ill in consequence of two severe Wounds on his Head - he is fit to be examined, Altho' I am of the Opinion he is somewhat Intoxicated". Given the gravity of the situation, why were there 'No proceedings'?

We read, "This is a most unintelligible case - The woman accused seems clearly to have been innocent & the injur'd person". The Crown Office opinions certainly give us a lot more insight into these cases!

Search these as part of Scotland's Criminal Database. If you find a case you can use our service or visit the National Record of Scotland and view the original records for yourself.

Crown Office Opinions - Duels did not always take place at dawn!

I have been investigating the AD13 records some more and having a lot of fun in the process. Known as Crown Office Opinions, they contain some hidden gems, particularly if your ancestor was accused of a crime but it didn’t go to trial. You can watch a short video here on YouTube if you missed this part of the conference.

I have found the case of a duel in December 1829. The declaration of George Baillie gives us an overview of the case (NRS reference AD13/274):

"At Edinburgh the Ninth day of December Eighteen hundred and Twenty Nine Years In Presence of George Tait Esqr. Sheriff Substitute of Edinburghshire: Compeared George Baillie, who being examined, Declares that on the Morning of Thursday last, the Third of December Current, the declarant was waited upon at his fathers residence at Mellerstain, by Mr. James Pringle, son of Sir John Pringle of Stichell; that Mr Pringle shewed the declarant a note from Captain Noel requesting Mr Pringle to meet him at Kelso With a friend stating that Captain Stewart was there, and Mr Pringle requested the declarant to accompany him as his friend and they accordingly immediately went together to Kelso where the Declarant was introduced to Captain Noel; that they conversed as to the cause of the dispute between Mr Pringle & Captain Stewart the two principals, about which the declarant declines to mention at present; that it was arranged that the principals and their friends should meet near the race ground at Kelso Within half an hour; and they all met accordingly, and no other parties were in sight at the time; that the Declarant and Captain Noel measured Ten paces, and the declarant & Captain Noel loaded the pistols With powder and a single ball, That they were Common duelling pistols. That each party received a pistol from the hand of his Second, and they took their stations; that the seconds retired a few paces, and the parties were informed that Captain Noel would give the signal which was to be "Make ready; Fire", That Captain Noel immediately have the signal; that the parties fired together; and Mr Pringle fell, & the Declarant ran to him, found that he was wounded in the thigh & bleeding profusely, brought a chaise which was standing at a short distance and along with which Mr Stewart a surgeon in Kelso was waiting; and they drove to the race stand at Kelso race ground where Mr. Pringle now lies; and Declares that every thing was conducted with the greatest fairness and honour on the part of all concerned and all this he declares to be truth".

Tantalisingly we do not seem to find out what the 'cause of the dispute' was because George declines to mention it. It was touch and go for a while. Medical reports tell us that James Pringle's life was on the line. The first dated 3 December 1829 reads, "I hereby certify that I have this day attended James Pringle Esquire of Stichel on account of a Pistol Shot which he received this forenoon, on the anterior part of his Thigh. - And I further certify that the Ball not being yet extracted I do not consider him free from danger. [Signed] John Stewart".

Another medical report dated the 4th of December tells us that he is still in danger. On the 5th of December we see a medical certificate signed by William Newbigging, Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. We are told that that 'Mr James Pringle eldest son of Sir John Pringle' is still in danger. On the 6th another medical certificate declares that James Pringle is doing well and that he is now 'out of immediate danger'. By the 14th James was still doing well and we are told that he is 'out of danger'.

The consequences? We see that George Baillie was examined and given bail under a penalty of £100, which was quite a substantial sum in 1829. A letter tells us that he was keen to be given bail rather than go to prison. Captain Stewart and Captain Stephen Noel were committed to the Jedburgh Castle Jail on the 3rd of December but released on bail on the 10th; after James Pringle was out of danger. By the 21st of December, it was decided to pursue the case no further.

As with other court records, the paperwork offers a fascinating insight into life at the time. As well as the accused we hear from the surgeon and John Halliday, chaise driver to Mr Adam Yule of the Cross Keys Inn, Kelso. John was aged 25 and happened to be involved because he was told to drive the chaise to Kelso. He probably had a more exciting day than he had been expecting. I wonder if he told his grandchildren all about it years later and they all thought he was making it up?

It has certainly been an exciting find for us and it is just one of many. I hope you find interesting records as you make searches in the days and weeks to come. This index is part of Scotland's Criminal Database.

Statutory Registers of Deaths - Death during construction of the Forth Bridge

In this video extract, archivist Tessa Spencer from the National Records of Scotland shares an interesting death register entry and shows us how to discover more about some death entries by using the Register of Corrected entries.

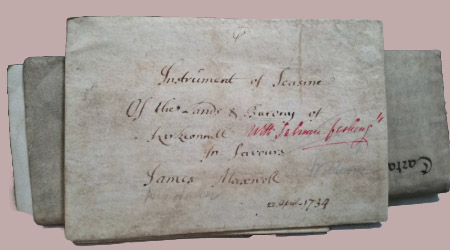

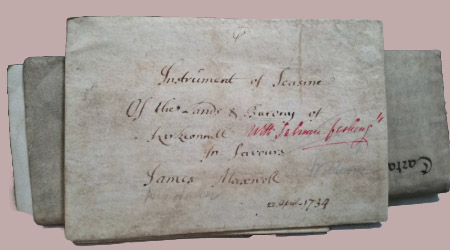

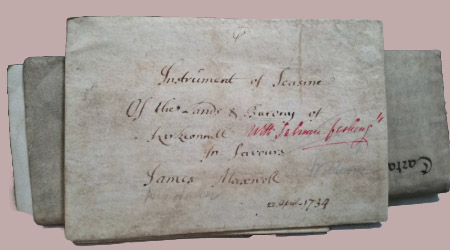

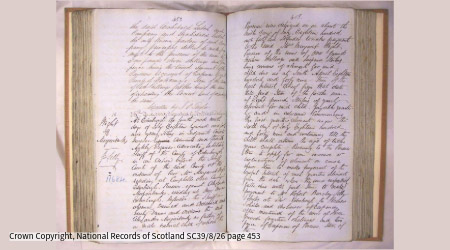

Register of Sasines - Finding Elizabeth's father

All too often it can feel like we have 'hit a brick wall' with our family history research. We perhaps feel that we have exhausted all surviving records but could we be missing some major record sets? Have you searched sasines?

Sasines are Scottish property records and apart from those registered in the Royal Burgh registers of sasines these have been indexed from 1781 to the present day. You can find out more here in our Learning Zone. For the earlier period, however, the indexing is patchy. When there is no index we use the minute books as finding aids. One minute book may cover several years and the brief summary is usually enough for us to determine if the entry relates to our family.

The great thing is that these documents name relatives and give relationships. Here is an example from Ayr from 4 August 1779 (National Records of Scotland reference RS66/9 p. 337):

"Air 4th August 1779 106. Seasine Elisabeth Faulds daughter of the deceast Tho[mas] Faulds of Hairshaw now spouse of William Gemmill of Waterside in liferent of an annuity of £5 Sterl[ing] with a Kitchen and a room or chamber adjoining thereto and a yeard of one rood of ground & that only during her widowity furth of the lands of Waterside Nether Aiker and Muirend all lying in the parish of Dunlop and Shire of Air proceeding upon a Contract of Marriage dated 16th March 1772 entered into betwixt her and the said William Gemmill was pres[ente]d by said Da[vid] McWhinny and reg[istere]d &c"

If we were researching this family it could be a challenge to know who the father of Elizabeth was but now we have a name and residence. Also, he is described as deceased so we know we are looking for a death before 1779.

Elizabeth is described as the spouse of William Gemmill and we learn that they have a marriage contract dated 1772, likely near the time of their marriage; a marriage which I cannot find in the church records.

This is all from the minute book! Of course, there may well be even more details in the register itself. There does not appear to be a will for Elizabeth on ScotlandsPeople, so we may presume she had few assets, but what we have learned here is that many people we do not expect appear in sasine records.

Do you want to keep learning about resources for Scottish family history research? Join us at the next Scottish Indexes Conference.